In the past, testing a vehicle was a fairly affair. Once a vehicle had proven it could handle the strains and stresses of the more extreme elements of daily driving, it was largely good to go. Outside of yearly check-ups and product recalls there was little reason to bring the examiner back in. However, in the world of autonomy, that approach does not fly.

In contrast to traditional vehicles, autonomous vehicles (AVs) are an ever-changing product. With each test run the vehicle’s artificial intelligence (AI) evolves, spotting things it never spotted before and highlighting new edge cases to be addressed. After decades of stability, ensuring these state of the art vehicles are tested productively is a huge challenge.

However, it is not a challenge that is deterring the industry; the Holy Grail of Level 4 and 5 autonomy is proving too big a prize to ignore. How the industry can design its testing procedures to reach these heights, though, is a tough question.

“Testing has fundamentally changed in the transportation ecosystem,” said Jeremy Bennington, Solutions and Technical Strategy Lead at Spirent Communications. Speaking at M:bility | Europe, a two-day conference hosted by Automotive World, Bennington observed: “Once the vehicle design was complete we did not really have to test after we’d manufactured. Now the car is a living, breathing, changing beast.”

Simulation

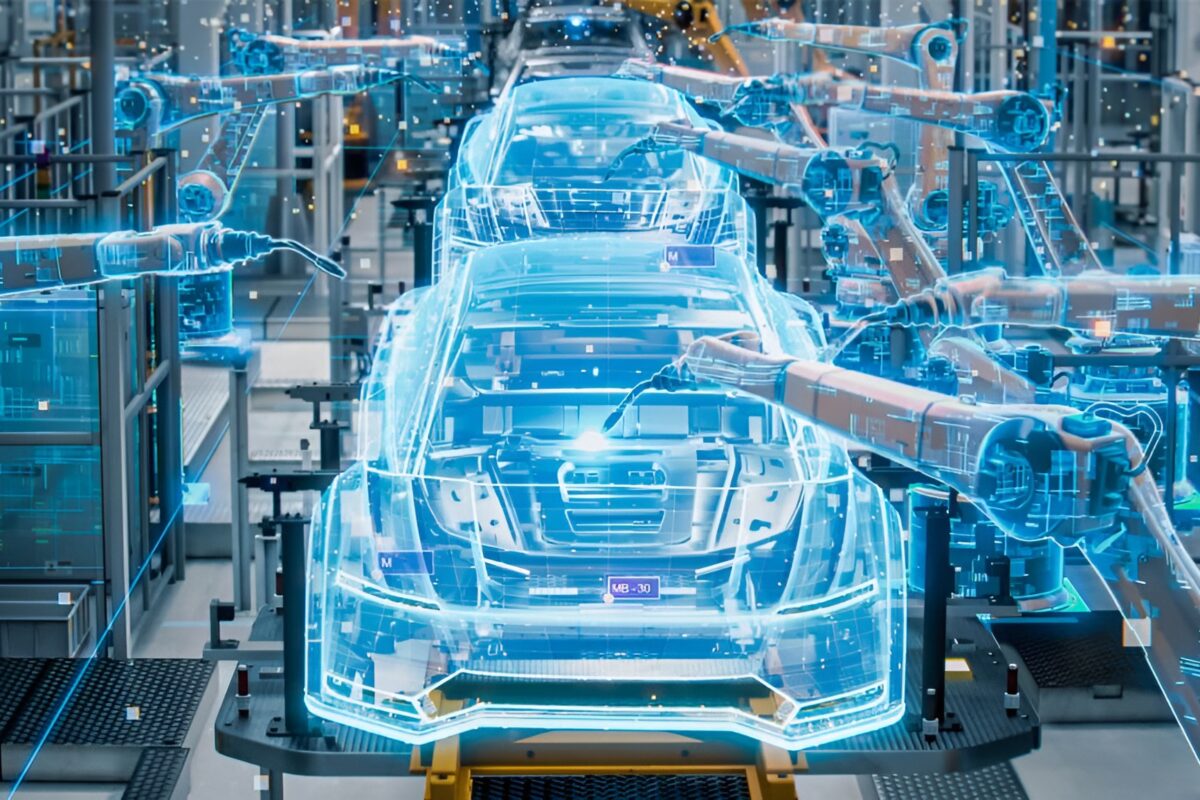

The inherent safety risks of autonomy, especially at its early maturity level, create a much higher burden of proof. While traditional test results are used to determine whether a vehicle will remain structurally safe over its entire product lifecycle, for the AV these tests are used to prove the competency of ever-changing computer code over millions of test miles. To tick this box, the industry has increasingly leaned on simulation. “We as an industry have to move to a developed, secure offering. Every time you’re adding a feature you have to simulate it,” said Bennington.

“Testing is now moving into the virtual environment which is safer, and there seems to be a consensus that simulation will play a fundamental role in all of this,” added Henning Lategahn, Managing Director at HD mapping company Atalec. “I do not know if this will be enough, however. It’s fair to say that we simply do not know how to truly validate an autonomous system.”

Once the vehicle design was complete we did not really have to test after we’d manufactured. Now the car is a living, breathing, changing beast

While this uncertainty remains, the industry is combining simulation and real-world testing. For instance, should an AV discover an edge case it cannot address in the real world, these scenarios can be recreated virtually by collecting positional and driving data. This reactive approach allows players to paper over the cracks in their systems as they appear.

“If we create digital twins then we can have continuous improvement of our simulation models and then roll out the features to the operation vehicle,” added Lategahn. “Simulation is not just a development tool.”

Testing framework

While testing practices are evolving, there remains a call for a testing framework which players can follow. Just as how human drivers are forced to undergo a well-defined test to determine whether they are capable of driving a car, many experts believe that a similar framework is needed to ensure continued practical AV development.

For instance, MCity, the University of Michigan’s private AV testing facility, has put together its own AV driving test concept. The ABC test includes three factors: ‘A’ refers accelerated evaluation, essentially testing with a ‘quality over quantity’ mindset when it comes to collecting test miles. ‘B’ stands for behaviour competency, where a fixed set of scenarios is assigned to an AV to determine its base competency level. ‘C’ covers corner cases, where an AV platform needs to show it can think on its feet when presented with an entirely new scenario.

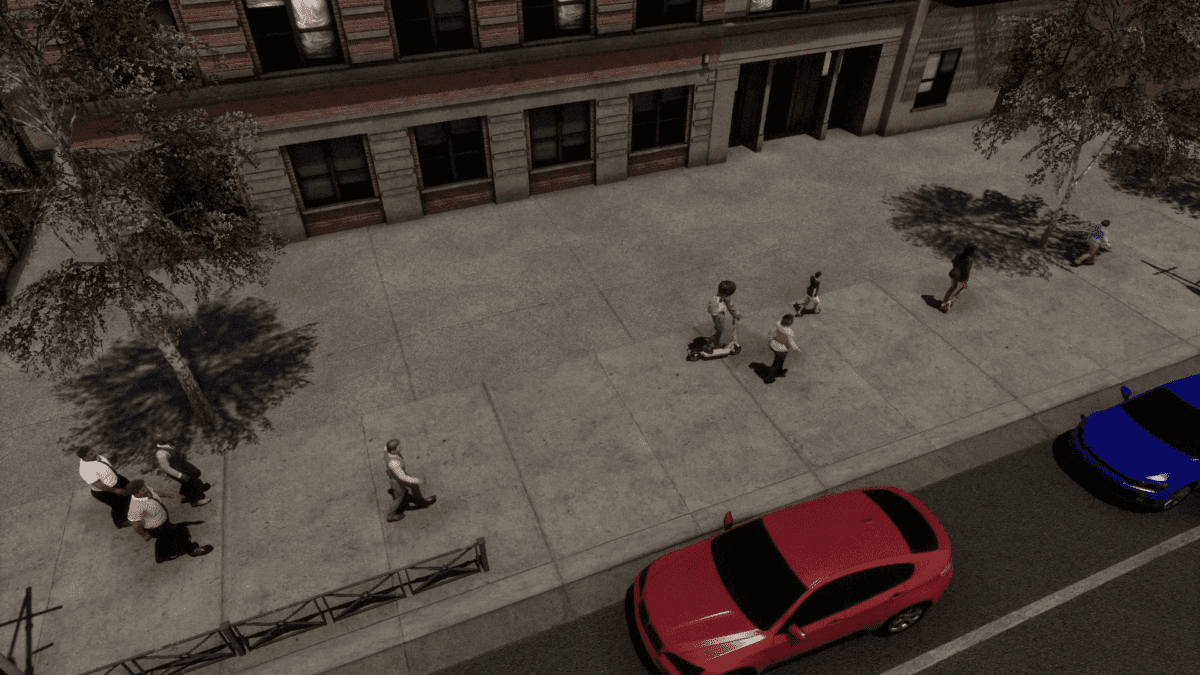

As Huei Peng, the head of MCity, explained to Automotive World, the hope is that the ABC concept can lay the groundwork for future test cycles. “When you go to a typical test facility the focus is on elements such as high-speed cornering, durability and how well a vehicle can go up and down a hill,” he said. “When we test we want to make sure that it is not only about the car but also the relative motion between the car and other road users.”

While this is a new way of thinking, Peng holds a firm belief that AV testing will quickly move down this route. “It will only be a matter of time before we say, ‘if you pass this test 50 times then we think you have demonstrated enough competence.’ It will not guarantee a crash-free environment because a crash is a two-party tango, but having this kind of testing in a safe place first is a must.” While the approach makes plenty of sense on paper, some fear that the automotive industry may restrict itself by treating an AV like a human driver.

We need to be careful what we test for as it could be an edge case for one AI but not another

“Very often we talk about these edge cases, but in certain situations these scenarios are edge cases for one system but not for another,” said Lategahn. “When the General Motors rear-end crashes started happening—in the first ten months of 2017 GM test vehicles were involved in 13 crashes in California, none of which were determined to be the automaker’s fault—there were so many companies out there saying that their AI system would have been able to handle that situation. I believe that this is probably true, but also that in other cases GM’s system would be able to tackle things that those critics’ platforms could not. We need to be careful what we test for as it could be an edge case for one AI but not another.”

Public safety dilemma

Another element to consider is that of public safety. While autonomy remains a core tenet of Vision Zero, achieving this goal will not be an incident-free process. The simple fact is that these early prototypes, while impressive feats of technology, are imperfect. Like it or not, crashes will happen. Ensuring that the public keep faith with autonomy in the wake of these incidents could be make or break.

“We cannot aim for perfection as it is just not possible,” said Lategahn. “There’s a bit of a dilemma because once we deploy these self-driving systems I would expect them to be safer, but there is likely to come a time when a self-driving car hits and kills a child. If that happens, we as an industry will have to try to explain to the parents that these vehicles are still good for society.”

Experience shows that this is likely to be a tough sell. For example, Waymo, which continued testing in Arizona following the 2018 Uber crash, reported 21 separate incidents where members of the public threatened or attacked its test vehicles—even though it had not been involved in the incident in question. These attacks ranged from tyres being slashed while the vehicles were parked to one man waving a .22 calibre revolver at a Waymo safety driver.

Once we deploy these self-driving systems I would expect them to be safer, but there is likely to come a time when a self-driving car hits and kills a child. If that happens, we as an industry will have to try to explain to the parents that these vehicles are still good for society

The wife of an Arizona resident, whose husband had been issued a police warning for attempting to ram Waymo’s vehicles off the road multiple times, told the New York Times that her husband “found it entertaining to brake hard” in front of a self-driving test vehicle. Worryingly she seemed to empathise with her husband’s mission—“they did not ask us to be part of their safety test,” she told the publication.

If autonomy is to continue enjoying practical development, the industry desperately needs to address this ‘us versus them’ mentality. “Part of it is about how we respond to human incidents, just like when an aeroplane crashes; it makes the news because a bunch of people die even though just as many people die from car accidents per day,” said Bennington. “We cannot predict what society is going to do but we can see the data and say that we can reduce not only the number of deaths but also injuries. We owe it to society to get these systems out as soon as we can.”

“In the automotive industry we are working towards Vision Zero, but it shouldn’t be Vision Zero it should be Mission Zero,” added Ahmed Yousif, Software Design Engineer at Valeo. “We need to save as many lives as possible but when we deploy a system we cannot guarantee that there will not be an incident. We need to provide as perfect a system as possible to achieve that mission.”

Certainly, autonomy appears on the cusp of great progress. With the easy wins now under the industry’s belt, huge steps could be taken over the next decade towards achieving Level 3, 4 and maybe even Level 5 autonomy. Making sure it keeps on track, however, will require more than just technical proficiency.

This article appeared in the Q4 2019 issue of M:bility | Magazine. Follow this link to download the full issue.