It is not news that electrified vehicles are in the ascendancy. By 2030, AlixPartners projects that battery electric vehicles (BEVs), plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) and hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) together will comprise 44% of the overall global light vehicle market, up from only 5% in 2018.

This growth in electrified sales is vital. Major markets such as Europe have committed to strict average CO2 reductions from newly registered vehicles, with penalties for those who fail to meet them. In Europe, starting 2020, a range-wide average CO2 target of 95g/km comes into effect. Automakers who exceed this face fines of €95 per gram of CO2 over target, per car sold. The annual fines for some large brands could run into several billions.

But even an aggressive roll-out of BEVs will not be the complete answer to hitting these targets, which will quickly become even more aggressive. By 2025, a 15% reduction on the 2021 figure must be achieved. By 2030, this grows to a 37.5% reduction. This is an average target figure of less than 60g/km. Electric cars are important—but so too are lower CO2 versions of conventional ICEs.

The importance of ice

The strategic role, and inherent value, of the internal combustion engine (ICE) can be easily overlooked in the electric excitement. However, even by 2030, four in every five new light vehicle sales will still rely on an ICE in some form meaning developments in combustion engine technology will be pivotal in the decarbonisation strategy of automakers.

By 2030, AlixPartners projects that battery electric vehicles (BEVs), plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) and hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) together will comprise 44% of the overall global light vehicle market

Yet to maintain an exciting, balanced and commercially viable portfolio of pure ICE and hybrid models, automakers must meet the challenge of recouping the rising costs of emissions-compliant ICE development. Compounding the challenge is the fact that they must balance this against a backdrop of shrinking model lifecycles that continue to be shortened by fast paced change in regulations and consumer preferences.

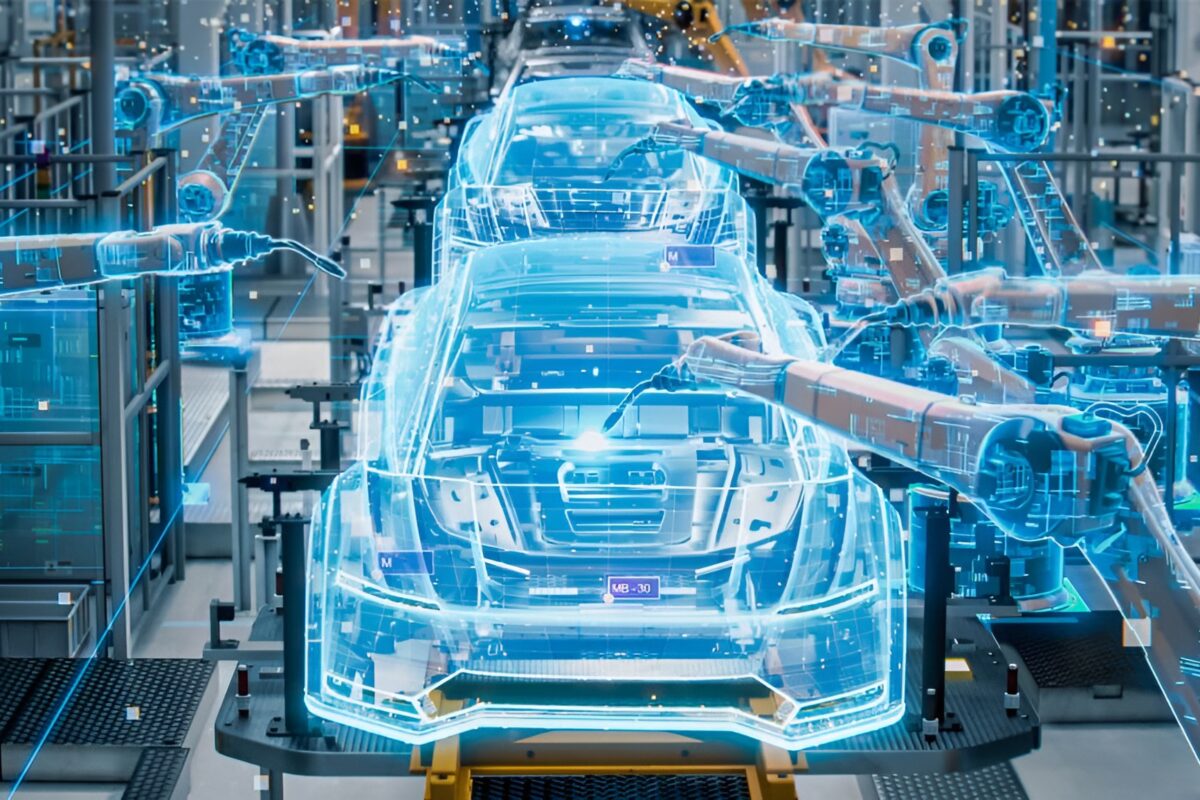

Sharing newly developed ICE technology across multiple vehicle platforms—and, most importantly, across hybrid platforms as well—helps to achieve this. By sharing ICE technology across both pure ICE and hybrid powertrains, automakers can achieve the higher volumes of sales needed to generate the necessary returns on engine investments and avoid scenarios of “stranded” powertrain investments. Automakers simply cannot keep producing ICEs without hybrids, and vice-versa.

We therefore expect hybridisation of ICE vehicles to accelerate, particularly with regular and 48V mild hybrid solutions. Hybrid electric is more affordable and more accessible than pure BEV or plug-in hybrid, and increasingly efficient.

Even by 2030, four in every five new light vehicle sales will still rely on an ICE in some form meaning developments in combustion engine technology will be pivotal in the decarbonisation strategy of automakers

Nowhere is this more poignant than for mass market smaller vehicles such as B-sector superminis and C-sector family-sized hatchbacks, where hybrid is a more effective mainstream strategy to expensive BEV drivetrains. We hold the view that, from 2023, battery pack manufacturing costs are likely to hit the US$100/kWh level indicating the likely point of production cost parity with ICEs. However, this holds only for all light vehicles on average—it does not apply to smaller B and C segment vehicles where battery pack costs will need to drop further to reach a point of parity.

Due to this cost and accessibility gap, the ICE and hybrid will also remain the answer for years to come in the markets that automakers are relying on for future growth—major emerging markets across Asia, Middle East, Latin America and, eventually, Africa. Cost will remain king in these lower per capita income markets, keeping the ICE firmly in its dominant position.

At the other end of the value scale – and building heavily on technologies increasingly honed in motorsport – premium and high-performance manufacturers recognise the combined merits of hybrid technology to deliver not just efficiency and pace but crucially the mechanical engagement and driving attributes intrinsic to their brand values.

Between 2019 and 2023, the cost of electrification alone may be US$225bn, equal to the amount automakers already commit on capital expenditure and R&D in total

Hybridisation is not the only trend making a future involving ICEs seem more possible and palpable despite tightening emissions regulations. Developments in terms of catalysis and sustainable drop-in fuels have also shown promise for bringing the industry closer to a “net-zero” emissions reality. When these are combined with hybrid powertrains, it is clear the industry surrounding the ICE still has a few more tricks up its sleeve.

Batteries: threats and anxieties

The hurdles for mass adoption of electric vehicles are, however, arguably more involved and fundamental. Automakers face considerable challenges in the supply of raw materials for batteries. For example, with approximately 50% of the world’s cobalt supply coming from a single country (Democratic Republic of Congo), the risks of supply chain bottlenecks and price fluctuations are significant. New reserves urgently need to be unearthed, given that there are also capacity constraints on nickel, another rare earth material used increasingly in today’s batteries, to ease the strain on the cobalt supply chain.

Consumers have more real-world concerns. Despite rising BEV real-world ranges, consumer ‘range anxiety’ persists, driven by weak charging infrastructure development. New EV models are being rolled out faster than charging points can be installed and before viable business models and the correct mix of fast and ultra-fast chargers can be established in all major markets. Until this develops further, consumers will remain reluctant to commit to a BEV at the final point of purchase despite many claiming good intentions when surveyed about their propensity to buy BEVs.

Carrot and stick

Bans on the sale of new ICE vehicles are coming, but not yet. England and Wales have a goal of 2040 for the ban on sales of new ICE petrol and diesel vehicles. France is also targeting 2040.

Far from being yesterday’s technology, the ICE still has an integral role to play in helping automakers secure the ROI they require to prosper in an ultimately all-electric future

Other countries are more ambitious. Scotland is targeting 2032; Sweden and Denmark say 2030; and Norway, where electric vehicles are already approaching 50% of the new car market, has set its target as 2025.

Ahead of that, cities are proposing their own regional ban on fossil fuel vehicles. Others are focusing on ultra-low emissions zones, in which all but the cleanest gasoline and diesel cars are charged to travel within them. Consumers face a stick; where is the carrot?

Heavy-duty haven

For heavy-duty (HD) vehicles, the ICE will continue to dominate for at least the medium term (today, over 98% of European new trucks are diesel), as fitting so many batteries to effectively serve the required range would restrict both carrying capacity and payload.

Recharging would be inconvenient and the up-front cost of purchasing an electric heavy-duty vehicle would be prohibitive for many businesses, due to the raw battery cost. The immaturity of a second-hand marketplace for electric HD trucks also means the potential repair costs and effective management of depreciation and resale values represent uncharted territory for fleet operators and lessors.

We expect hybridisation of ICE vehicles to accelerate, particularly with regular and 48V mild hybrid solutions

A ‘hub and spoke’ solution for logistics companies is the most likely scenario. ICE heavy-duty vehicles will run long distances between hubs, where they are at their most efficient, with smaller electric commercial vehicles transporting loads from these hubs into those cities which place restrictions on ICE vehicles.

Bridging the profit desert

Electrification requires enormous investment by the automotive industry. This is in addition to investment in other technology, known as CASE: Connected, Autonomous, Shared, Electric. AlixPartners research has previously stated the automotive industry is likely to enter a ‘profit desert’ due to the massive investment required.

Between 2019 and 2023, the cost of electrification alone may be US$225bn, equal to the amount automakers already commit on capital expenditure and R&D in total. The need for such considerable investment may last for an extended period of time, potentially placing hundreds of thousands of jobs at risk.

Electric is the future, but the careful and deliberate evolution of the ICE is how automakers will get there. Progressive investment in transferable platform technology that can be shared across both regular ICE models and hybrids will help spread risk and generate faster returns as model life cycles shrink further. Far from being yesterday’s technology, the ICE still has an integral role to play in helping automakers secure the ROI they require to prosper in an ultimately all-electric future.

About the author: Sean O’Flynn is a Managing Director in the Automotive practice at consultants AlixPartners