Today’s transportation industry faces numerous technology-enabled challenges. Truck makers are faced with the need to develop autonomous, electrified and fully connected vehicles. The ever-increasing expectations of young e-commerce customers require new logistics concepts which translate into more stringent KPIs for logistics providers as well as new vehicle concepts. Big data, blockchain and other technologies promise to create increased efficiency in the logistics supply chain. This efficiency and transparency will increase overall delivery speed but has the potential to erode margins. Major new players such as Amazon threaten to disrupt incumbent players. Clearly, there are plenty of challenges and opportunities which could keep fleet operators, 3PL providers, truck makers and other participants in the logistics value chain up at night.

The rate of adoption of various technologies varies. Connected trucks and telematics are table stakes for truck makers, although a convincing revenue and profit model still seems somewhat elusive. The use of electric trucks will be enforced by regulation in the EU, in China and maybe in some US states. However, electrified trucks have only a very limited number of profitable use cases given the current cost and incentive structures, and are likely to drain cash from truck maker operations for some time to come.

Daimler and partner Torc Robotics began testing Level 4 autonomous trucks on public roads in September in North America. Earlier this year, Amazon invested in Aurora and was rumoured to be interested in taking over TuSimple

Autonomous trucks, on the other hand, provide a clear business case to fleet operators and hence truck makers based on our calculations and assessment. To examine this, we need to break down the truck’s task in terms of a total, revenue-generating journey. At the point of consignment, it is loaded, it then travels the distance necessary to reach its point of discharge where it is unloaded. In much the same way as a plane takes off, flies at cruising altitude and then lands again, the point at which human intervention is most necessary is at the start and the end of the journey; the distance between the point of loading and point of discharge may be ten miles or 1,000 miles (1,609km), but irrespective of this the variables that lie within this part of the task are amenable both to reduction and thus ultimately to automation.

At present, truckload freight tends to travel either on a point-to-point basis—as described above—or via a relay system in which trailers are swapped at terminals. Hence a load may be accompanied by the same driver for the duration of the journey, or that same journey may involve multiple drivers.

The use of a terminal-based relay system already offers operational advantages and, by our analysis, is a key enabler for the adoption of autonomous trucks. While it is difficult to see the driver eliminated from the initial and final stages of a truck journey, it is entirely possible—and indeed entirely logical both from an operational and a financial perspective—to automate the middle stage—the part of the journey that constitutes the bulk of the mileage.

While technology for autonomous operations should be ready by 2025, the key challenge for participants in this space is public acceptance

While this middle stage of the journey is likely to be the most time-consuming part of the entire task, it is—arguably—that part of the task which is least productive. Freight generates revenue by being collected and delivered; when it is sitting on a trailer it is not generating but enabling revenue. It is—effectively—the first and the last mile that counts for everything.

What, then, is the likely future model of a truckload journey involving an autonomous truck? It bears a striking similarity to current intermodal methods of transport whereby a trailer—or a container—is collected from a point of loading and then delivered to a railhead. From here, it is transported by railcar to a corresponding railhead close to the point of delivery where, once unloaded, it is delivered by a conventionally driven truck. In our model, we see the railcar replaced by an autonomous vehicle while the drayage task is still fulfilled by a conventional staffed vehicle.

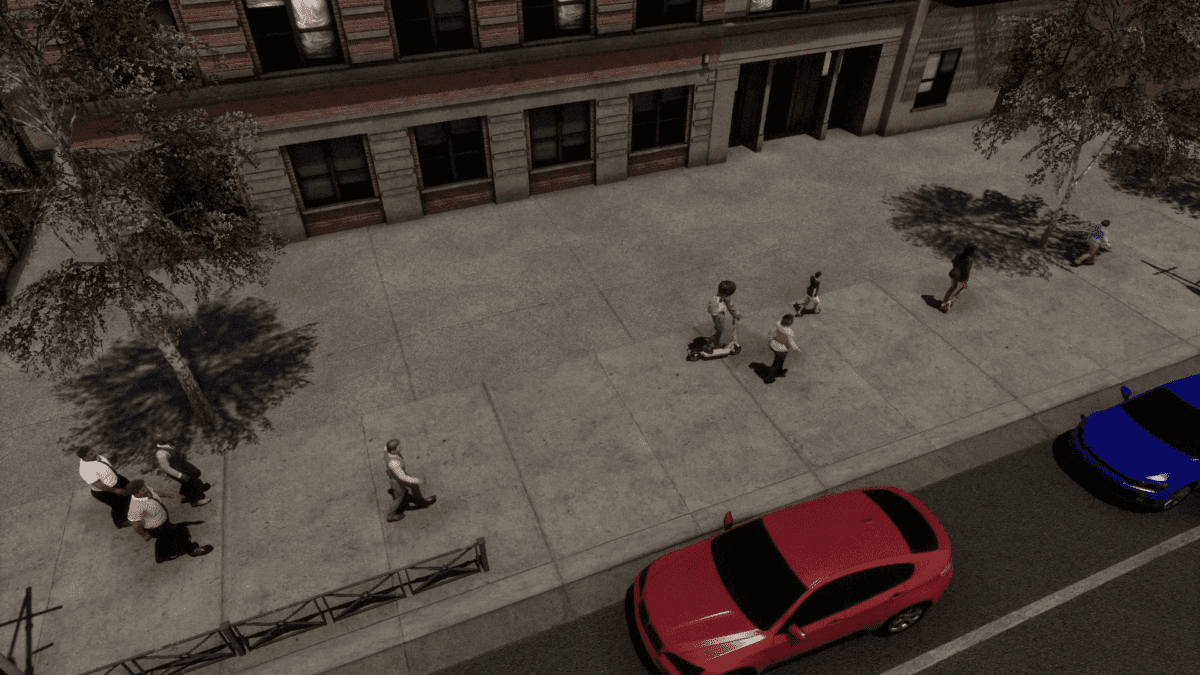

There are a number of advantages attached to this approach. Drivers are still central to the task, but they become inherently more productive; a driver can collect and deliver multiple loads on a daily basis and—importantly from a recruitment and retention perspective—that same driver can be home-based. The terminal-to-terminal approach does require acceptance of autonomous trucks on public highways but does not involve autonomous trucks driving in crowded cities with the sometimes unpredictable behaviour of traffic participants. Last but not least, logistics costs are dramatically reduced—by up to 38% based on our hub-to-hub models—which benefits consumers (albeit not necessarily the environment).

Without public acceptance, the investment in autonomous trucks will not pay off

Hence consistent investment in autonomous trucks continues apace. For example, Daimler and partner Torc Robotics began testing Level 4 autonomous trucks on public roads in September in North America. Earlier this year, Amazon invested in Aurora and was rumoured to be interested in taking over TuSimple.

While technology for autonomous operations should be ready by 2025, the key challenge for participants in this space is public acceptance. Voters have to be comfortable to share public highways with trucks without drivers. One way to address their concerns is to demonstrate increased safety and reduced accidents by operating autonomous trucks. This will require a large number of test miles that are successfully driven.

Without public acceptance, the investment in autonomous trucks will not pay off. For example, assuming that autonomous trucks will only be allowed to ply in the front runner states Arizona and Florida, only 0.9% of all US freight would be carried by autonomous trucks. A meaningful penetration would require at least all sunbelt states to adopt legislation that allows commercial operation of autonomous trucks. In such a case, about 23% of all US freight would be carried on autonomous vehicles, which in turn would imply that about 500,000 autonomous trucks would be part of an overall fleet of 3.9 million trucks. In addition, the US trucking industry would require more than 1 million new drivers entering the profession based on such a scenario, i.e., automation would alleviate but not eliminate the pressures of truck driver availability.

Autonomy as well as other disruptive trends will have ramifications along the OEM value chain. As cab-less trucks emerge as a new sub-segment, the truck manufacturers will have to find new ways to differentiate their product offering

What does this all mean for incumbent truck makers? Autonomy as well as the other disruptive trends that we have mentioned earlier will have ramifications along the OEM value chain. As cab-less trucks emerge as a new sub-segment, the truck manufacturers will have to find new ways to differentiate their product offering. The provision of after sales services to autonomous trucks will require tight integration of autonomous trucks with the OEM service network via connectivity and predictive maintenance solutions. Increased investment in vehicles is likely to drive fleet consolidation, which will necessitate improved solution selling capabilities of the sales network. Procurement will need to find ways to extract value from a supply base that is likely to add even more value and own more IP than in the past. Manufacturing will have to adjust capacities to reflect the higher utilisation of automated trucks. New business models such as Truck-as-a-Service could be explored. Increased funding requirements for developing new technologies while not jeopardising the existing core business will drive new partnerships and co-opetition between OEMs in much the same way as we have observed in the passenger vehicle space.

While traditionally conservative, the commercial vehicle industry is caught in a perfect storm, compounded by global uncertainties on the geopolitical and trade front. Pressure testing strategies and operational models for agility and flexibility have become the new norm.

About the author: Dr. Wilfried G. Aulbur (wilfried.aulbur@rolandberger.com) is Senior Partner and Member Supervisory Board at Roland Berger

This article appeared in Automotive World’s November 2019 ‘Special report: The path to the autonomous truck – 2019 edition‘, which is available now to download