Securing the connected car will require hefty investment and collaboration, but it doesn’t have to be a reinvention of the wheel. Companies that can draw on experience from other industries will not only find themselves ahead of the competition but also pull forward development efforts for all players.

Spread the burden

To start with, companies along the supply chain are going to need to work together. “There is no one vehicle manufacturer on the planet that will be able to take on the challenges of automated driving, safety and security, by itself. The investment is too great and the market is moving too fast,” warned Marques McCammon, General Manager of Connected Vehicles Solutions at Wind River. “You are going to see more collaboration between the OEMs to make sure that they can find solutions that all of them can use to spread the expense and the business risk of moving into these new technologies.”

He points to the recent collaboration between BMW, Audi and Daimler, which came together to invest in HERE for high definition mapping. McCammon suggests this move “was a direct strategy to hedge their brand positions against the Google brand position.” It’s not just the OEMs, though, that are pulling out all the stops as they scramble to adjust to new software requirements.

Standards: the next big focus

Wind River has been applying learnings and expertise from other industries. The company, an Intel subsidiary specialising in embedded software, has built up know-how in mission critical industries that require fail-safe technologies. The Boeing 787 Dreamliner, for instance, uses its VxWorks 653 real-time operating software platform. VxWorks also provides the core operating system of the spacecraft control system in NASA’s Mars Rover, Curiosity.

It is this sort of experience that sparks its calls for an industry-wide standard on software. “In the aerospace, industrial and defence industries, public and private sector agencies and corporations came together to create software standards that everyone could design to,” McCammon pointed out. “They maintained the openness of the standards in a way to preserve competition between the constituents. After all, competition drives innovation.”

In aerospace, for instance, ARINC 653 (Avionics Application Standard Software Interface) sets out the software specification for space and time partitioning in safety-critical real-time operating systems. For the defence industry, the FACE approach represents a government-industry software standard and business strategy for the acquisition of affordable software systems, designed to facilitate fast integration of portable capabilities across different defence programmes around the world. “All of these standards created some normalcy around the way that the whole industry approached software, which de-risks it and spreads the investment across all the constituencies,” McCammon told Megatrends. “There was still enough openness in the community to allow those who service these industries to compete and to drive innovation. This will be the next big wave of discussion in the automotive space, and I firmly intend for Wind River to be in the middle of it.”

The many faces of security

For Wind River, to be ‘in the middle of it’ is to play at the heart of cyber security for connected vehicles – and that security comes in many forms. One of the most straightforward is personalised information management, namely the ability to bring consumer information to the vehicle and control it in such a way that it is not easily accessible to outsiders.

“Going forward, the vehicle will have more and more access to the driver’s personal information. It has moved far from the basic notion of a driver profile that emerged in the late 1990s or early 2000s, when you enter the car and pushed a button and the seats and the steering wheel would move to your desired position. Nowadays you come into the car and the vehicle recognises you as the driver and brings up your music list, your contact information, your key points of interest on your map, the location of your home and your place of business,” he elaborated.

The more this sort of connectivity – the same sort that is present on mobile devices – comes into the car, the more the industry opens itself up to the potential of someone gaining access to that information. Well-publicised white hat hacks have spread that message clearly.

There is no such thing as bug-free software. It becomes a very real point of concern if you put that into the context of a 3,500 pound hunk of metal and plastic hurtling at speeds of up to 150mph

Additional challenges come as the car takes on more software-based functions. “The notion of more vehicle functions defined in software, and the fact that there is connectivity to the vehicle at various if not all points in time, means that there is potential for someone to gain access to the vehicle in whole or in part,” warned McCammon. “If I want my vehicle to have connectivity it entails a threat vector for someone to enter into that vehicle and to take action.”

Transformational risks and opportunities

Software in general brings with it safety risks. “There is no such thing as bug-free software,” McCammon emphasised. With smartphones or laptops, updates are relatively quick and painless but it’s not so straightforward for vehicles. “It becomes a very real point of concern if you put that into the context of a 3,500 pound hunk of metal and plastic hurtling at speeds of up to 150mph,” he observed. This is where over-the-air updates come into play, offering an essential means of managing that update process. “It becomes a way for us to mitigate risks and to make real-time corrections to vehicle functions and software as we go forward.”

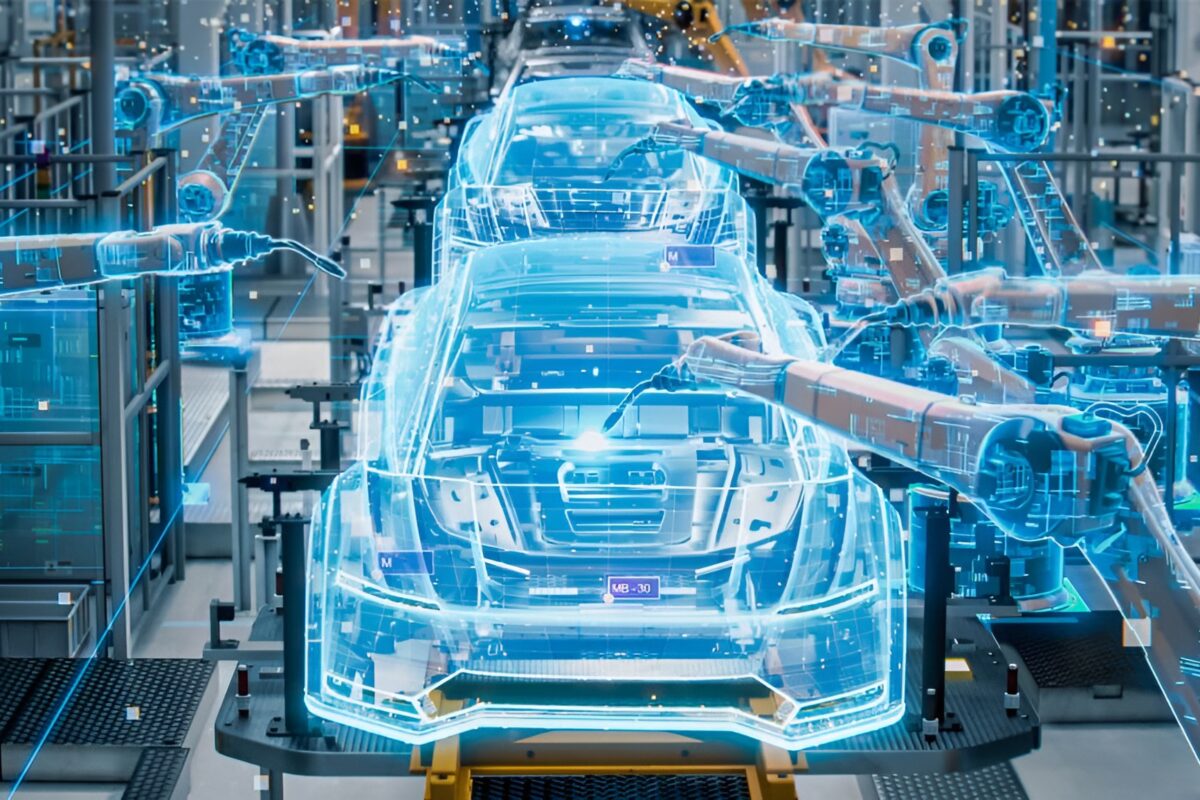

While software brings new risks into the vehicle, it also brings new potential

and capability to the vehicle and McCammon regards it as something as transformational to the industry as the introduction of the mass production assembly line. “We are at an inflection point and software is at a critical part of that inflection,” he explained. “With any transformation, the change that it brings can mean risk and opportunity. If it is not managed properly then the notion of risk overshadows the notion of opportunity. As an automotive community, we need to be open about what the transformation means and be cognisant of where the risks and opportunities are.”

Autonomy ups the game

McCammon regards the move towards autonomous driving as an extension to the security concerns today. “What becomes a factor as we look at security is the level of computing that we talk about with automated driving. It is going to be vast. We’re talking about data centres and terabytes of data in minutes. You need to be able to make sure that this is maintained, controlled and made secure so that information provided to the vehicle is the best possible information at every point in time. You need to ensure it cannot be corrupted,” he said. “If there is any new introduction of threat, that will be it because many of the algorithms will not necessarily live on the car.”

A handful of commitments have been made for launching self-driving vehicles, and ensuring their safety by this time is essential. At just a few years away, some of these deadlines may seem impossible. “2020 and 2021 are key dates for automated driving,” said McCammon, but these don’t necessarily mean wholesale, high volume production of automated vehicles. “I would expect to see controlled fleets of vehicles in highly manageable environments, which would allow the industry to learn what it doesn’t know. Historically, when the industry has brought in new technologies, it typically is pretty measured.”

Electric vehicles (EVs) offer one example. “In the 2004-2005 timeframe, we saw each of the vehicle manufacturers doing very limited, very controlled pilots of EV technology in select markets with a select customer base,” he noted. “This afforded tremendous amounts of data capturing and collection so that they could prepare themselves for the next wave of product rollouts, which came three to five years later.”

He expects a similarly prudent approach on the autonomous roadmap: “They will be spending considerable time in testing to ensure that they can qualify and quantify the risks both from a safety and security standpoint.” And, he adds, “Wind River, with its experience and advice gleaned from other industries, will be there to help.”

This article appeared in the Q1 2017 issue of Automotive Megatrends Magazine. Follow this link to download the full issue.